The core.async library is a well known library in the Clojure community for managing asynchronous programming. It is based on CSP or Communicating Sequential Processes, originally introduced by Tony Hoare in a 1978 paper. The fact that core.async is based in CSP is oft-mentioned in core.async introductions. But why should we care?

CSP as a mathematical modeling language has a long and rich history in academic research. But as a developer trying to Get Things Done, does CSP matter? Once a library written in CSP exists, is there any reason for users to care about the underlying CSP concepts? And are there practical reasons that a library based on the CSP language is useful in ways that, say, a functional reactive programming or actors library is not?

Rich Hickey, in the blog post introducing core.async, hints that there are. He talks about building upon the work of CSP and its derivatives and states that “CSP proper is amenable to certain kinds of automated correctness analysis”. Edsger Dijkstra, in the introduction to Tony Hoare’s CSP book, describes the CSP approach in glowing terms as showing the way to “what computing science could– or even should–be”.

Tickled by the possibility of upgrading my mental tools, I looked through Hoare’s CSP book. The book is well written. It presents a mathematical language for describing communicating processes, along with low level examples of how different forms of communication could be modeled.

Reading through the book, I felt as though there was some profound understanding to be had in the CSP language, but the understanding itself eluded me. The examples were very low level. It seemed like a fine theoretical abstraction that was too difficult and time consuming to apply to practical problems. I put the book back on my mental shelf, forgot about the promise of CSP, and went to the store to solve a more practical problem: getting groceries.

A practical problem: Keeping groceries in sync

Getting groceries sucks. Everyone has to do it, thinking about food takes mental energy, and the process is error prone and sometimes stressful. Most people fall back on simple strategies to make grocery shopping work. They get the things they always get, or they painstakingly write out and maintain paper grocery lists.

There are other solutions in this problem space, but my idea was to write a real-time synced grocery list web app. You add items to the list from recipes and everyone sees them immediately. You can split up in the grocery store with your buddies or wife and check off items as you find them. Everyone sees the whole time what is left to get. You all get out of the store quicker.

How do I keep these items in sync? That’s simple. Every time something changes, we send the change to everyone else. As every software developer knows*, the network is fast and reliable and available so the changes will make it through immediately and everyone will stay in sync.

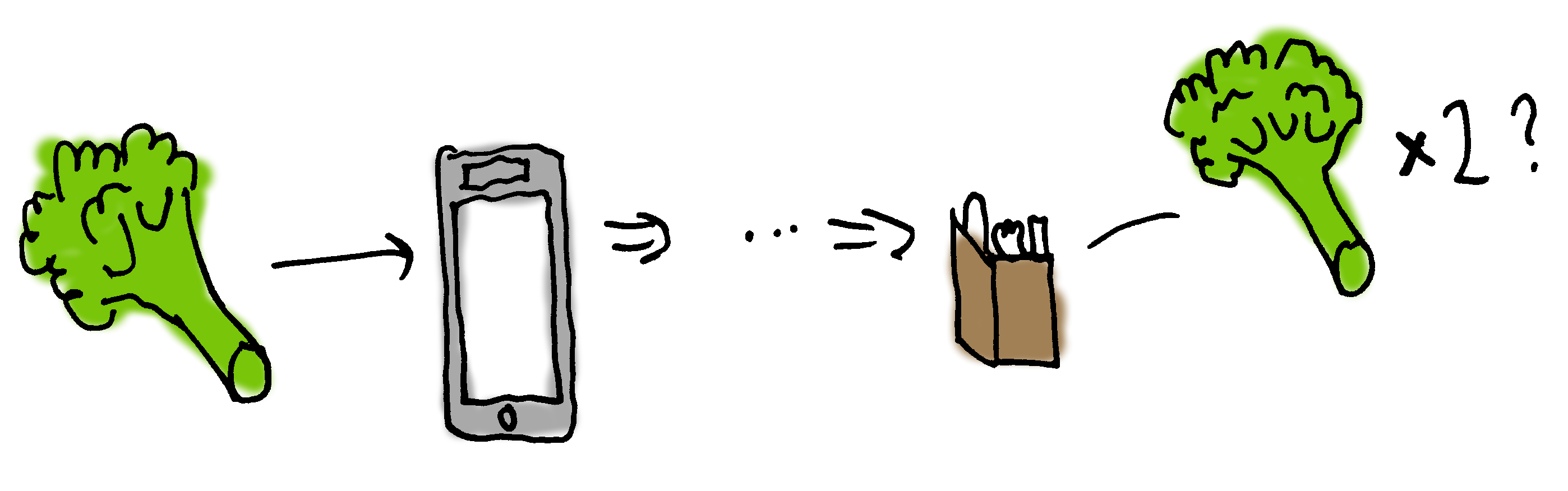

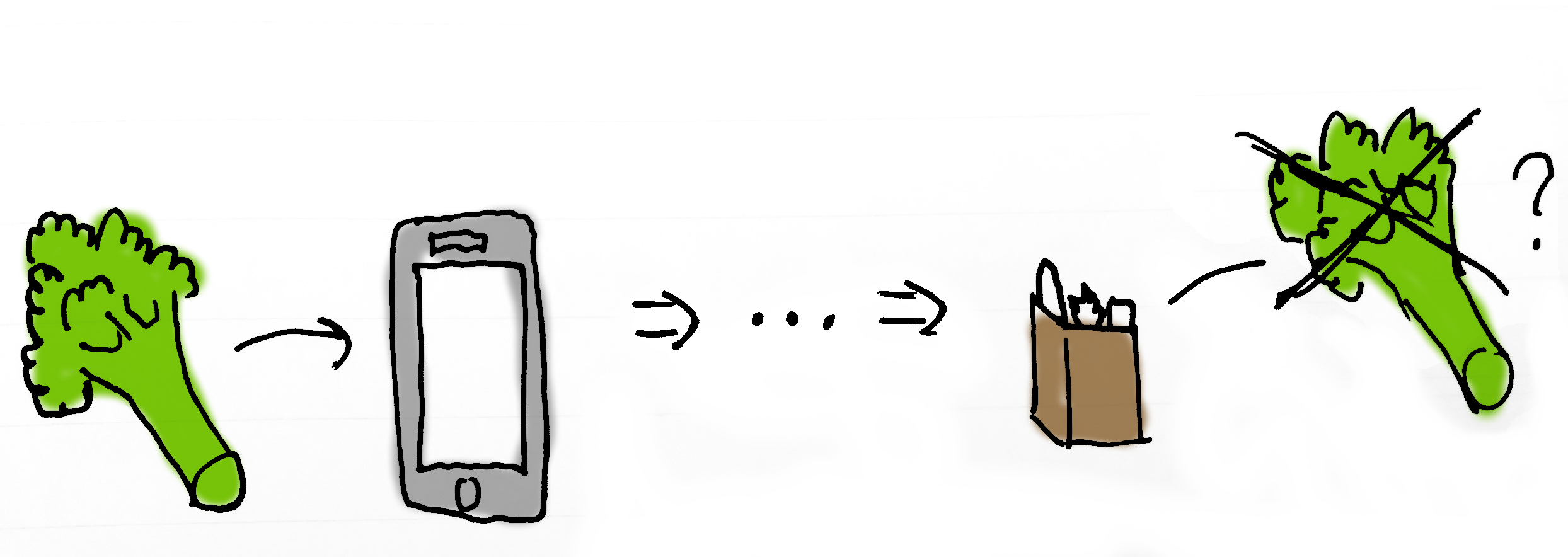

This poor man’s solution actually worked remarkably well. Until it didn’t. My child would press something on my phone while I was weighing broccoli and I would lose my Internet connection and end up getting twice as many tomatoes as I needed, because my wife had picked them up while I was disconnected. The blue cheese would disappear from the list under mysterious circumstances. Mistakes were made. The dinner table suffered. Test users (my wife and two year old) didn’t appreciate my explanations about the complexities and prohibitive costs of proper synchronization algorithms for a small unfunded product development team.

Worst of all is the uncertainty. You’re never quite sure if everything is still on the list, or if items have been mysteriously “lost”, or if items that you check off have already been checked off by someone else. This is clearly not a proper solution for a software developer (nor a software developer’s wife).

I hunted around for better solutions to my sync problems. I could make everything synchronous, but that would be slow and only work online. Operational transformations developed for text-based collaboration sounded promising but probably more complex than necessary. Finally I settled on differential synchronization, described in a 2009 paper by Neil Frasier of Google.

Learning by implementing papers: Differential sync

Differential sync had a number of aspects that felt like a good fit for my use case. Everyone can edit all the time without blocking others. Local states naturally converge in an “eventually consistent” sort of manner. Finally and perhaps most importantly, someone had written a coherent paper that explained how to implement it.

How differential sync works

The basic approach in the client-server setup works as follows. Client and server start out in the same state. Both client and server maintain their own state and a “shadow” state representing the last synced state from the other party. When changes are made on a client, a diff is computed between the new state and the shadow state. The diff is tagged with the client and server versions that it is based on and sent off to the server. The server verifies the version numbers, patches the changes onto its own state and its shadow client state, and then compares the two. If there are differences, i.e. someone else made changes on the server in the meantime, the two new states are diffed and the diff is sent back to the client. Repeat ad infinitum. Go ahead and read the paper, it’s actually quite well written.

This is a simple idea on the face of it, but as always, the devil is in the implementation details.

How my implementation works

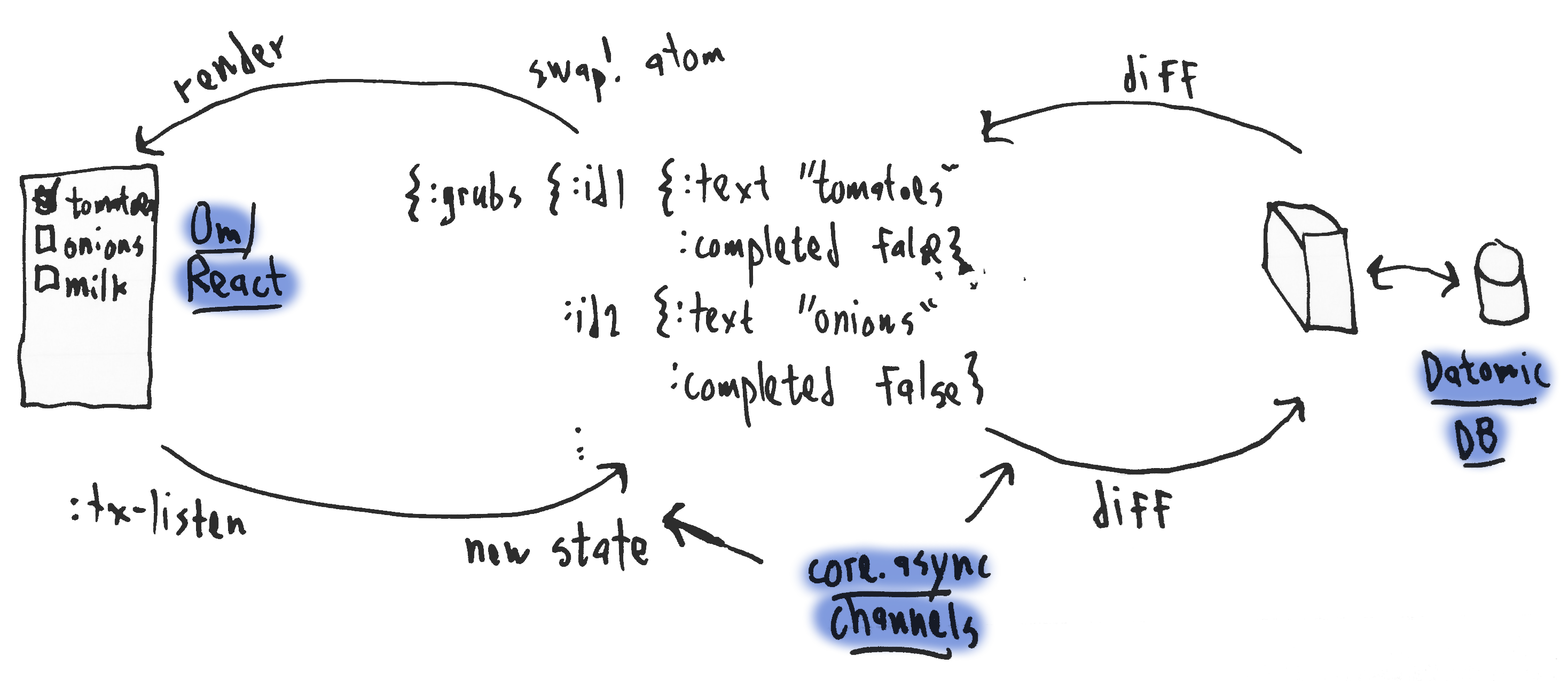

I implemented this as a Clojure and ClojureScript web app. You can try it out here 1 and read the source here. The front end uses Om for the UI and is connected via WebSocket to a Clojure backend, which persists changes to a Datomic database. Synchronization is handled by a client-side core.async process (go block) communicating with a server-side core.async process. To update the UI when the state changes, it passes the new state to a Clojure atom and through Om/React magic the UI is re-rendered efficiently. To capture all UI state changes, it uses a nifty feature of Om that allows one to observe all UI data changes. We pass these via a core.async channel to our our client synchronization process.

The diffing and patching algorithm works as follows. Both client and server start out in the same state containing a list of our grocery items, which I refer to as “grubs”:

{:grubs { "id1" {:text "2 cans cherry tomatoes" :completed false}

"id2" {:text "cream" :completed false}

"id3" {:text "4 T. red pesto" :completed false}

"id4" {:text "1 yellow onion" :completed false}

"id5" {:text "2 T. brown sugar" :completed false}

"id6" {:text "1 garlic bulb" :completed false}

"id7" {:text "cottage cheese" :completed false}}}

When one client makes some changes

{:grubs { "id1" {:text "2 cans cherry tomatoes" :completed true} ;; completed

;; removed "cream"

"id3" {:text "4 T. red pesto" :completed true} ;; completed

"id4" {:text "1 yellow onion" :completed false}

"id5" {:text "2 T. brown sugar" :completed false}

"id6" {:text "2 garlic bulbs" :completed false} ;; edited

"id7" {:text "cottage cheese" :completed false}

"id8" {:text "milk" :completed false}}} ;; added

we compute the diff of these changes and send it on to the server:

{:grubs {:+ {"id1" {:completed true}

"id3" {:completed true}

"id6" {:text "2 garlic bulbs"}

"id8" {:text "milk" :completed false}}

:- #{"id2"}}}

The diff tells which items were added or modified under the “:+” map and the IDs of items that were removed under the “:-“ set. To update the server state, we then run through the diff and merge in the changes to the server state. Merges happen on a “last edit wins” basis.

How Clojure makes this nice

I want to stop for a moment to point out how elegantly the whole process works using Clojure. Diffing and patching is handled in a straightforward and relatively efficient manner using Clojure’s immutable data structures. UI updates are just a render call with the latest state. By using core.async for communication between our sync processes, our sync processes don’t actually care that the communication is going over the network. They take in messages and send out messages and all that matters is the type and timing of messages. This also makes it straightforward to test. We connect the processes directly to each other, spoof messages as necessary, and verify that the processes shoot out the correct messages.

Finally, storing the data in a Datomic database, which I had not used before, has been pleasant and has interesting properties. Datomic is an immutable data store. It works similarly to Clojure’s data structures in preserving the history of changes while using structure sharing for performance.

Having the entire history of changes instantly makes the grocery app much more valuable. It allows me to do things like look over my entire history of grocery shopping and see how often I cook burgers in a month. The app could suggest items to add to grocery lists based on items I have previously purchased. It could make recommendations based on users who have similar tastes.

This together with the fact that changes are synced immediately also has other interesting implications both from technical and privacy perspectives. You can derive a lot of personal information from this kind of data. You could analyze the timing of when items are completed to organize the grocery items by store section. You could find out when people shop for groceries, when they think about groceries, what they eat, what time zone they live in, how their tastes have changed, or how many times they change their mind about broccoli and end up getting a premade meal instead. Immutable data unlocks compelling possibilities but can also have serious privacy implications.

Another interesting property of using Datomic as a data store is from the synchronization angle. In a normal synchronization setting you would have to store a certain amount of history and sync clients from this history. If the client state is older than the history, then you would have to do a full sync, losing all changes from the client. With Datomic we have the entire history of changes. We can do a sync from any historical state of the database. In practice you would probably want to do a full sync for older client states anyway, but the idea is compelling.

If I had to implement this project in JavaScript, the complexity may have killed me well before this point. One way to do it would be to basically reinvent Clojure in JavaScript: use ImmutableJS or Mori for immutable data structures, use BaconJS streams to communicate events, separate React rendering and app data and use a single event loop in order to render and capture changes, and use event sourcing or the like to keep a history of database events. This would be a much more difficult project to tackle. Using Clojure makes it possible to tackle complex problems that would otherwise be too much trouble.

Why sync was still difficult

Even using Clojure, I ran into my own challenges with implementing the differential sync algorithm. The paper sometimes lacked detail. My use case was not identical to the paper’s use cases. My own architectural decisions did not always agree with the paper’s approach. As my implementation strayed from the strait and narrow path drawn by the paper, it became more and more uncertain whether the implementation worked.

In particular, I ran into the following challenges:

- The paper assumes a traditional polling-based HTTP request model. The paper’s algorithm only allows one packet in flight at a time and otherwise seems to imply a traditional HTTP request based model. I had wanted to use WebSockets in order to receive changes from other clients as quickly as possible. It is unclear whether these two thoughts are compatible.

- The paper assumes the server will keep the shadow state for a client even if the client is not connected. The paper does not describe the process of initialization, but assumes the client and server are in a “connected” state throughout (although packets may be lost). This means the server must maintain a representation of the client state even when the client is disconnected. This feels like an unreasonable restriction.

- Code complexity. This synchronization requires careful coordination between sync processes and the UI and database. Refactoring core.async processes can also be more difficult than normal refactoring because go threads are implicit and used through macros (which have different scoping rules).

My implementation seemed to work, but after all was said and done I was left with a nagging feeling of uncertainty. The uncertainty that had plagued me with my initial ad hoc approach to synchronization was creeping back. Grabbing pepperoni slices from the grocery store freezer I was plagued by the thought that I was forgetting something. I checked and double-checked that blue cheese had made it onto the list. I asked my wife to show me her own list at times to see if my list looked the same. The lists did match. Except sometimes, inexplicably, they didn’t.

How can I know that my sync algorithm works?

I tried different tactics to overcome this uncertainty. One of the basic problems is that the problem was too large to easily think about. Error cases occurred in very distinct scenarios, and it was too difficult to know if changing one aspect of the algorithm would affect a completely different scenario.

I tried finding ways to represent the problem in a more conceptualizable manner. I drew diagrams and wrote out possible synchronization scenarios on paper. I thought about using statecharts or other diagramming languages to represent the problem more clearly.

I wrote test cases to verify that different aspects of the synchronization algorithm worked correctly and to verify that the big picture worked if you hammered on it. But testing concurrent code is fundamentally broken. You can write test cases. You can pull up many browsers and have them all hammer on the app and randomly disconnect and connect and see that the browsers end up in the same state. This helps you feel more confident, but ultimately it only tests a small part of the problem space. Concurrent errors may depend on very specific timings of events. How do you know if synchronization works in all cases?

In short I had failed. I didn’t feel more confident about my implementation of differential sync than I had felt about the ad hoc approach. I blamed Neil Frasier for not thinking his algorithm through completely. I blamed my implementation, which had grown in complexity and was difficult and time consuming to verify. I blamed core.async, which had failed me in my moment of need. But the thought nagged me that there had to be a better way to handle this problem. I needed to be able to write my own algorithm. I needed to upgrade my mental tools.

And I remembered the promise of CSP.

This post is duplicated on both my blog and the Reaktor blog.

Footnotes

-

Go ahead and use the app if you like. I try not to break things but this is a hobby project so there are no guarantees. Different URLs correspond to different lists, which are synced independently. ↩