How does one know if their synchronization algorithm works? I have a real-time synced grocery list app. In the last post I attempted to scrape by on synchronization by implementing differential sync based on an intelligent-sounding paper. In the end my implementation had subtle bugs and was difficult to debug. I hoped to find a better approach to the problem using the CSP language.

One challenge is just to make the problem understandable. If the CSP language can represent the problem clearly and succinctly, it already makes it easier to manipulate the algorithm, discover problem cases, and implement it properly. But can CSP actually prove that synchronization works? And perhaps more importantly, is it worth the effort?

CSP and CSPM

CSP has a long and rich history in research and there are doubtless countless uses and resources of which I haven’t the foggiest. The books I found that I liked were Roscoe’s “The Theory and Practice of Concurrency” and Steve Schneider’s “Concurrent and Real Time Systems: the CSP approach”, in addition to The CSP Book from Hoare himself. But the important thing for me came from Roscoe’s book, which introduced me to the CSPM language.

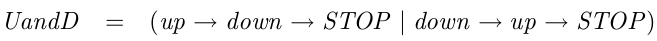

CSP is a mathematical language for representing processes that talk to each other. It allows you to model problems and then make assertions about those models. Modeling can be useful, as it helps you think about the problem, and assertions are grand. If you can make it work. Eventually. But to me this felt difficult to apply and not very well scalable to more complicated problems.

But CSPM, as it turns out, is just a programming language. It’s a modern programming language, inspired by languages like Miranda and Haskell. But don’t be too worried if Haskell doesn’t inspire. It is a much stripped down and focused version of this.

So instead of writing intricate mathematical algorithms, we can just write programs and debug and test them. Better still, the CSPM “IDE”, the FDR3 CSP refinement checker, comes with a REPL. You can write algorithms like you write code, load it into the REPL, explore it visually, and tweak it and see if it still compiles and passes assertions. Let’s try it out.

A simple algorithm: syncing broccolis with CSPM

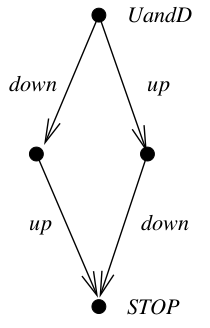

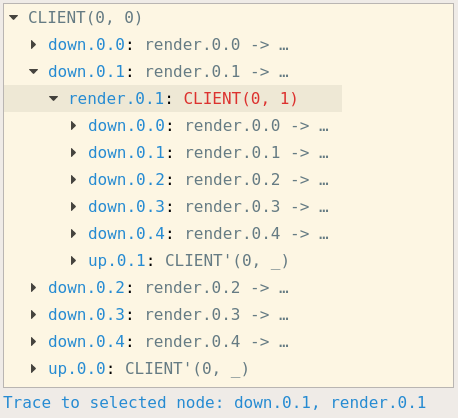

The goal is to keep grocery list items in sync between different clients, connected to a central database via one or more servers. Here is what the algorithm looks like, using broccoli:

The rest of this section walks through representing the broccoli algorithm using CSPM. You can follow along by downloading FDR3 and my complete CSPM program and opening the program using FDR3 (“fdr3 sync.csp”). Useful FDR3 commands to start out: :help to see what commands are available and :reload to reload the current file after changes have been made.

Client sync process

NUM_CLIENTS = 2

NUM_DB_STATES = 5

CLIENTS = {0..NUM_CLIENTS-1}

TIMES = {0..NUM_DB_STATES-1}

channel up, down, render:CLIENTS.TIMES

CLIENT(i, t) =

up!i!t -> CLIENT'(i, t)

[] CLIENT'(i, t)

CLIENT'(i, t) =

down!i?server_t

-> render!i!server_t

-> CLIENT(i, server_t)

For the client, I define two different processes which essentially behave as one process: CLIENT and CLIENT’. The CLIENT process either uploads a diff to the server when the user performs an action or behaves just like the CLIENT’ process. The CLIENT’ process takes a diff from the server, renders it, and then behaves like the CLIENT process. The t variable represents the client’s state and is incremented each time data is saved to the database. The client process has three events it can engage in: up, down, and render. Each event has a client number associated with it to identify the client and a state representing the database “time”.

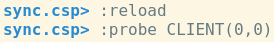

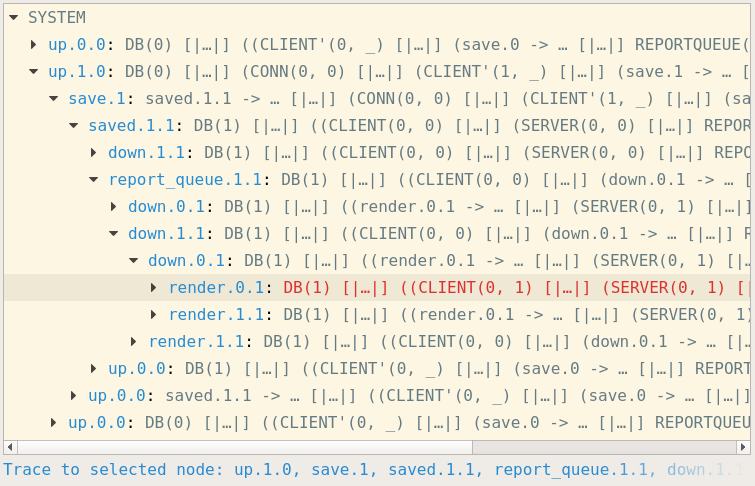

How do we know if we implemented the process correctly? You can interactively explore the states of the process using :probe CLIENT(0, 0), which gives you a dialog like this:

The probe dialog shows the possible actions our process can engage in at any given state. It’s easy to run through the diagram, try out different scenarios, and assure oneself that the process works how it was supposed to.

Server sync process

SERVER(i, client_t) =

up!i?server_t

-> save!i

-> saved!i?new_server_t

-> down!i!new_server_t

-> SERVER(i, new_server_t)

[] report_queue?j:diff(CLIENTS,{i})?new_server_t

-> if new_server_t == client_t

then SERVER(i, client_t)

else down!i!client_t!new_server_t

-> SERVER(i, new_server_t)

The server sync process does two things. First, it takes in input from the client via the up event, saves it to the database, and sends any remaining changes back down to the client. Second, it reads in changes from other clients via (our representation of) the Datomic report queue and sends them down to the client, if they haven’t already been handled.

Database process

DB(t) =

save?i

-> saved!i!next_t(t)

-> DB(next_t(t))

REPORTQUEUE(i) =

saved?j:diff(CLIENTS,{i})?t

-> REPORTQUEUE'(i, j, t)

REPORTQUEUE'(i, j, t) =

saved?j':diff(CLIENTS,{i})?new_t

-> REPORTQUEUE'(i, j', new_t)

[] report_queue!j!t -> REPORTQUEUE(i)

The database process DB is very simple. It takes a new state to save from the server sync process i and saves it, returning the id t representing the database after being saved. The report queue process REPORTQUEUE takes these saved events and puts them in a sliding buffer of size 1 for other server sync processes to consume. This is how changes are passed from one client to another. It is a sliding buffer of size 1 because we only care about the latest state of the database. If we don’t have time to process an event in between it doesn’t matter - we just diff with the latest state we have available and send that down to the client.

Process wiring

Finally, everything is wired together in the end.

SERVER_WITH_REPORTS(i, t0) = (SERVER(i, t0) [|{| report_queue |}|] REPORTQUEUE(i))

CONN(i, t0) = CLIENT(i, t0) [|{| up.i, down.i |}|] SERVER_WITH_REPORTS(i, t0)

CONNS(t0) = [| productions(saved) |] i:CLIENTS @ CONN(i, t0)

SYSTEM = DB(0) [|{| save, saved |}|] CONNS

All processes start with an initial state t=0. The CLIENT process communicates with the SERVER process with the up and down events. The server process in turn communicates with the REPORTQUEUE process via the report_queue event. Each client/server connection pair, represented by the CONN process, receives saved events synchronously from the database. Finally, all of the connections communicate with the database via the save and saved events.

Putting it all together

As I left out a few details, here is the full example:

NUM_CLIENTS = 2

NUM_DB_STATES = 10

CLIENTS = {0..NUM_CLIENTS-1}

TIMES = {0..NUM_DB_STATES-1}

channel up, down, render, saved, report_queue:CLIENTS.TIMES

channel save:CLIENTS

next_t(t) = (t + 1) % NUM_DB_STATES

CLIENT(i, t) =

up!i!t -> CLIENT'(i, t)

[] CLIENT'(i, t)

CLIENT'(i, t) =

down!i?server_t

-> render!i!server_t

-> CLIENT(i, server_t)

SERVER(i, client_t) =

up!i?server_t

-> save!i

-> saved!i?new_server_t

-> down!i!new_server_t

-> SERVER(i, new_server_t)

[] report_queue?j:diff(CLIENTS,{i})?new_server_t

-> if new_server_t == client_t

then SERVER(i, client_t)

else down!i!new_server_t

-> SERVER(i, new_server_t)

DB(t) =

save?i

-> saved!i!next_t(t)

-> DB(next_t(t))

REPORTQUEUE(i) =

saved?j:diff(CLIENTS,{i})?t

-> REPORTQUEUE'(i, j, t)

REPORTQUEUE'(i, j, t) =

saved?j':diff(CLIENTS,{i})?new_t

-> REPORTQUEUE'(i, j', new_t)

[] report_queue!j!t -> REPORTQUEUE(i)

SERVER_WITH_REPORTS(i, t0) = (SERVER(i, t0) [|{| report_queue |}|] REPORTQUEUE(i))

CONN(i, t0) = CLIENT(i, t0) [|{| up.i, down.i |}|] SERVER_WITH_REPORTS(i, t0)

CONNS(t0) = [| productions(saved) |] i:CLIENTS @ CONN(i, t0)

SYSTEM = DB(0) [|{| save, saved |}|] CONNS(0)

So now we have a model representing our implementation. This is not the simplest model we could have come up with, nor is it the most complex. There are a lot of details that we left out. Client-server connections are not actually synchronous, even though we represent them as so. There is a certain amount of buffering in the system that is not modeled. We consider the diffing and patching algorithm only in very vague terms, passing around a single variable t to represent the database state. We don’t represent the possibility of lost packets or of the client disconnecting. We don’t represent users making changes as a separate event, instead tying it in directly to the moment the changes are sent to the server via the up event.

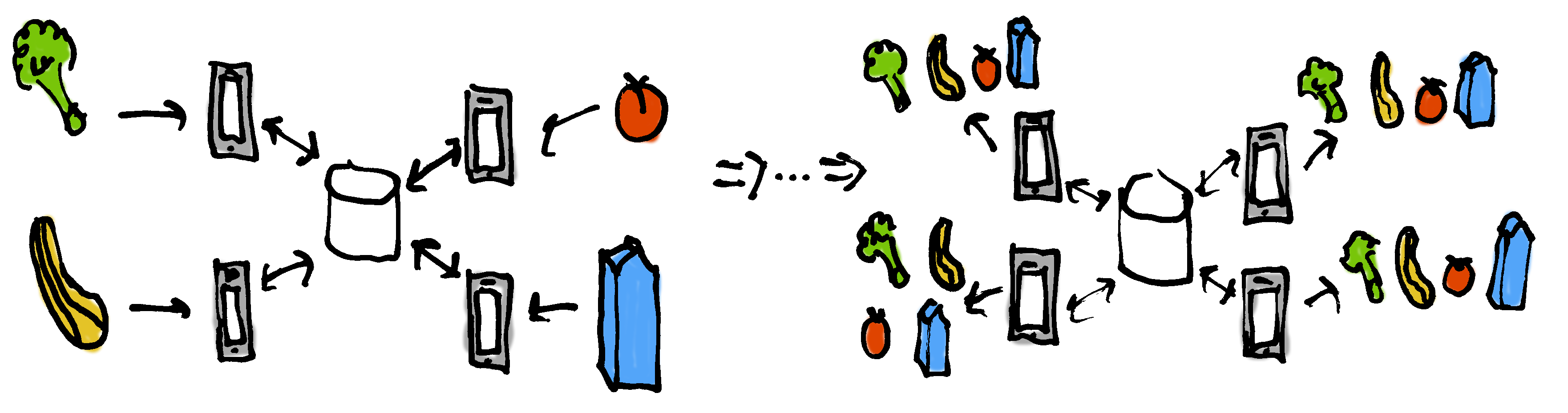

This is a simplified representation of the problem but already a useful one. Our algorithm is concise and unambiguous. We can visualize the algorithm and iteratively exploring the states of the algorithm using FDR3’s :probe SYSTEM.

But beyond that, this allows us to prove things about our algorithm.

Proving synchronization works: Sync one broccoli

What would we like to say about our algorithm using this model? Well, we want to prove that syncing “works”. What does it mean for syncing to “work”? Let’s start simple. Syncing works if I enter a broccoli on my phone and, at some point later, my wife sees broccoli on her phone. No other users or vegetables are involved.

How can we verify this using our CSPM model?

1) Allow only one change from one client

First, we want to restrict our implementation to allow only a single change from a single user. We do this by defining a processes that perform according to this specification and then forcing our implementation to synchronize with these processes on the relevant events.

Our first process restricts the implementation to only a single change:

MaxInputs(0) = SKIP

MaxInputs(n) = up?i?t -> MaxInputs(n-1)

The MaxInputs process performs n changes from any client i and then stops. If we set n=1 then it only allows one change. The question mark in up?i?t indicates that we are taking in i and t as inputs, which in this case we ignore. The SKIP event represents successful termination of the process.

A second process specifies that the input must come from a specific client:

OnlyClient(i) = up!i?t -> OnlyClient(i)

The OnlyClient process takes in inputs infinitely, but only from client i. The important syntactical difference here is in up!i?t. The exclamation point indicates that we are forcing i to be the specified client i i.e. only the one client is allowed to make changes.

To force our algorithm to behave according to these constraints, we tell it to synchronize with our constraint processes on the up event:

OneInputFromClientZero = (OnlyClient(0) [|{| up |}|] MaxInputs(1)) [|{| up |}|] SYSTEM

The system can only engage in up events when both of our other processes are ready to engage in up events. Thus the system is only allowed to take in a single input from client 0 and then cannot take any more inputs. Our constraints only affect the inputs, so it can still freely do whatever else that it wants, like upload to the server or save changes to the database. To verify that our constrained process works properly you can explore it with :probe OneInputFromClientZero.

2) Assert that the change makes it to the other client

Now, we want to show that a change on client 0 will make it to client 1. What does this look like from the outside i.e. what sequence of events would we expect to see if this works? We would expect to see an input/upload event from client 0 followed by a render event from client 1: <up.0.0, render.1.1>. In between a bunch of other events happen that we don’t care about right now.

Here is a process that does that:

SyncOneInput = up.0.0 -> render.1.1 -> STOP

The SyncOneInput process is our specification. This is how we hope our system will behave. We hope it will take input from client 0, render the state on client 1, and stop.

Finally, we prove that our system fulfills this specification by asserting that it does:

assert SyncOneInput [FD= OneInputFromClientZero

\diff(Events, union(productions(up.0), {render.1.1}))

What we assert here is that our constrained implementation OneInputFromClientZero must behave according to our specification SyncOneInput. If our specification takes in one input and sends it up to the server, our implementation must take in one input and send it up to the server. If our specification then, at some point after this, renders a new state on the other client, our implementation must also at some point render a new state on the other client.1

We can run the assertion through FDR3 and see that it works. Syncing one broccoli works. This is like a simple end to end test for our algorithm. But let’s make it more interesting.

Proving synchronization works: Sync many vegetables

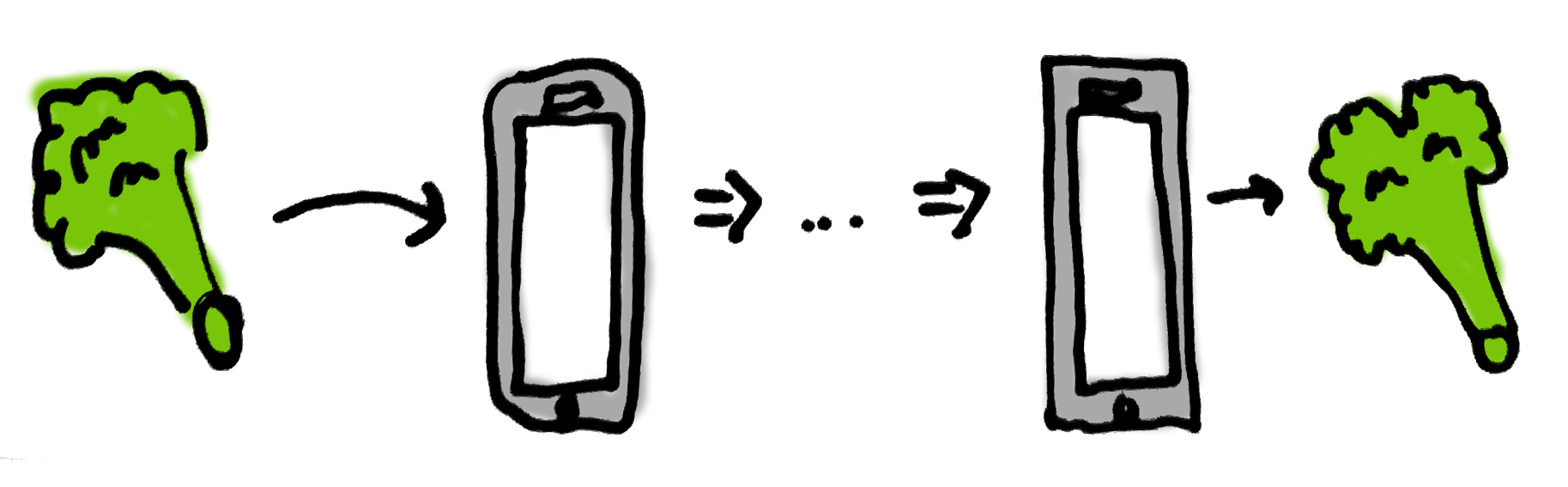

This app isn’t very useful if it only sends one broccoli from one person to another. What if I throw in tomatoes and my wife throws in milk and our friends who are visiting want zucchini and butternut squash?

Instead of only allowing one client to make a single change, let’s allow any client to make any number of changes, up to maximum number of changes. They stop adding things at some point. Then we verify that each client properly renders the final changes. This is essentially a definition for eventual consistency.

First, we need to allow a larger number of inputs n instead of just one input. We can use our MaxInputs process from above:

MaxInputSystem(n) = SYSTEM [|{| up |}|] MaxInputs(n)

Next, we need to define what we actually want to see in our specification. If the system is restricted to n inputs, what we would like to see after all of the inputs have been entered is for each of the connected clients to render the final state. For example, if 9 inputs are allowed, we allow 9 inputs from arbitrary clients and then expect to see all of the clients to render the state after 9 changes i.e. engage in the render.i.9 event. Conceptually this is still a very simple specification, though the syntax gets more involved:

sequences({}) = {<>}

sequences(a) = {<z>^z' | z <- a, z' <- sequences(diff(a, {z}))}

renderAll(sequence, t) = ; i:sequence @ render!i.t -> SKIP

SyncAll(n) = |~| i:CLIENTS @ up!i!0 -> SyncAll'(n, n-1)

SyncAll'(n, 0) = |~| renderSeq:sequences(CLIENTS) @ renderAll(renderSeq, n); STOP

SyncAll'(n, m) = |~| i:CLIENTS, t:TIMES @ up!i!t -> SyncAll'(n, m-1)

Without going into the syntax, this allows input nondeterministically in any order from any client and then requires them all to render the final state in nondeterministic order.

The final assertion can be run with FDR3 and it passes. We can even change the number of clients from two to four and see that it still passes.

assert SyncAll(9) [FD= MaxInputSystem(9)

\diff(Events, union(productions(up), {render.i.9 | i <- CLIENTS}))

What have we proved here? A similar end-to-end test might work as follows. We pull up four browsers. We randomly make n changes on a random window, stop for some period, and then verify that all of the browsers end up in the same state. This is a useful test. It shows that the system, including the parts outside of the algorithm, works in this specific situation. It means you probably didn’t screw up anything majorly.

But ultimately that test is also very limited. It randomly tests one single possible timing of events out of a huge space of possible timings of events. The exact behavior of the system, and whether it works or not, may depend on very specific timings. The test only tests one of these timings. The next time it runs it tests a different timing of events. Even if it fails, we have no good way of repeating the test. We just know that our system is “broken”. Somehow.

Our CSP assertion is much more powerful than an end-to-end test. Instead of testing one specific situation, it tests every single combination of timings that can occur with our system and says that in all cases our system will end up in sync. If the assertion passes, we know that the algorithm should work for any timing of events. If the assertion fails, it provides a single clear example of a sequence of events that causes the assertion to fail.

Conclusion: Does my sync algorithm work?

Our “eventual consistency” assertion says that given n connected clients, if we allow them to arbitrarily make k changes, eventually all clients will render those changes and stop changing. In this case I tested it with 4 clients and 9 changes, but this can be arbitrarily adjusted to any number of clients or changes as long as computing power suffices. On my computer two clients take a moment to verify, three take 36 seconds, and four take over twenty minutes. The parameters can be adjusted until you’re sure that the algorithm actually does work.

Note some of the things that this assertion does not say. It does not make any claims about timing. In theory synchronization could take a huge (finite) number of steps. Nor does not make any claims about the diffing/patching algorithm itself. We just assume it works.

The second, important part of verifying that the sync algorithm works is to make sure that the model actually represents our app in the important ways. It doesn’t help to write one model and implement another. It’s also easy to overlook real world aspects of the system like buffering or disconnections. Some of these could be handled simply enough outside of the model, as long as our model assumptions hold. Others might need to be included into the model.

Because the Clojure core.async library is based on CSP, it is a straightforward process to translate our model into Clojure. My final sync algorithm as it currently stands looks as follows.

Client sync process (source)

(defn sync-client! [initial-state to-server ui-state-buffer diffs full-syncs connected ui-state]

(go (loop [client-state initial-state

server-state initial-state

awaiting-ack? false]

(let [channels (if awaiting-ack?

[diffs full-syncs connected]

[diffs full-syncs connected ui-state-buffer])

[event ch] (a/alts! channels)]

(when DEBUG (println event))

(when-not (nil? event)

(condp = ch

full-syncs (let [{:keys [full-state]} event]

(reset! ui-state full-state)

(when DEBUG (println "Full sync, new ui state tag:" (:tag @ui-state)))

(recur full-state full-state false))

ui-state-buffer (let [new-ui-state @ui-state]

(if (state/state= server-state new-ui-state)

(recur server-state server-state false)

(do

(when DEBUG (println "Changes, current ui state tag:" (:tag new-ui-state)))

(>! to-server (event/diff-msg server-state new-ui-state))

(recur new-ui-state server-state true))))

diffs (let [{:keys [diff]} event]

(if (= (:shadow-tag diff) (:tag server-state))

;; Our state is based on what they think it's based on

(let [;; Update server state we are based on

new-server-state (diff/patch-state client-state diff)

;; Apply changes directly to UI

new-client-state (swap! ui-state diff/patch-state diff)]

(when DEBUG (println "Applied diff, new ui tag:" (:tag new-client-state)))

(when DEBUG (println "Applied diff, new server tag:" (:tag new-server-state)))

;; If there are any diffs to reconcile, they will come back through input buffer

(recur new-client-state new-server-state false))

;; State mismatch, do full sync

(do (>! to-server (event/full-sync-request))

(recur client-state server-state true))))

connected

;; Need to make sure we are in sync, send diff

(do

(when DEBUG (println "Reconnected, sending diff"))

(>! to-server (event/diff-msg server-state @ui-state))

(recur client-state server-state true))

(throw "Bug: Received a sync event on an unknown channel")))))))

(defn start-sync! [to-server new-ui-states diffs full-syncs connected ui-state]

(let [ui-state-buffer (chan (a/sliding-buffer 1))]

(a/pipe new-ui-states ui-state-buffer)

(go (<! connected)

(>! to-server (event/full-sync-request))

(let [full-sync-event (<! full-syncs)

initial-state (:full-state full-sync-event)]

(reset! ui-state initial-state)

(sync-client! initial-state to-server ui-state-buffer diffs full-syncs connected ui-state)))))Server sync process (source)

(defn start-sync! [list-name to-client diffs full-sync-reqs db-conn report-queue]

(let [id (rand-id)]

(go (loop [client-tag nil

awaiting-state? true]

(let [channels (if awaiting-state? [full-sync-reqs diffs] [full-sync-reqs diffs report-queue])

[event ch] (a/alts! channels)]

(when-not (nil? event)

(condp = ch

diffs

(let [{:keys [diff shadow-tag tag]} event

client-shadow-db (d/as-of (d/db db-conn) shadow-tag)

client-shadow-state (db/get-current-db-state client-shadow-db list-name)

a (debug-print (str id " " "Got diff from client: " shadow-tag " -> " tag))

{:keys [db-after]} (db/patch-state! db-conn list-name diff)

new-tag (d/basis-t db-after)

new-state (assoc (db/get-current-db-state db-after list-name) :tag new-tag)

new-shadow (assoc (diff/patch-state client-shadow-state diff) :tag tag)

return-diff (event/diff-msg new-shadow new-state)]

(debug-print (str id " " "Send diff to client : " tag " -> " new-tag))

(>! to-client return-diff)

(recur new-tag false))

full-sync-reqs

(let [current-db (d/db db-conn)

current-tag (d/basis-t current-db)

current-state (assoc (db/get-current-db-state current-db list-name) :tag current-tag)]

(debug-print (str id " " "Full sync client to : " current-tag))

(>! to-client (event/full-sync current-state))

(recur current-tag false))

report-queue

(let [tx-report event

new-db-state (:db-after tx-report)

new-tag (d/basis-t new-db-state)]

(if (>= client-tag new-tag)

;; Already up to date, do nothing

(do (debug-print (str id " " "Got report " new-tag " but client already up-to-date at " new-tag))

(recur client-tag false))

;; Changes, send them down

(let [new-state (assoc (db/get-current-db-state new-db-state list-name) :tag new-tag)

client-db (d/as-of (d/db db-conn) client-tag)

client-state (assoc (db/get-current-db-state client-db list-name) :tag client-tag)]

(debug-print (str id " " "Got report, send diff to client: " client-tag " -> " new-tag))

(>! to-client (event/diff-msg client-state new-state))

(recur new-tag false))))

(throw (Throwable. "Bug: Received an event on unknown channel")))))))))I think it works. I have a few niggling doubts about the interaction between buffering and the diffing algorithm. But if it doesn’t work, I have a solid way to make it better. It might not work because the implementation doesn’t match the model, in which case I update one or the other. Or it might be that the model itself is flawed. If the model is flawed, I should be able to write an assertion that fails and then change the model until it does not fail. All of these changes build on each other. The model can be iteratively improved without the need to start over from the beginning.

Try it out here. Pull up two browsers on the same URL and see if they sync. Use it for your family grocery run. If it doesn’t work, let me know. Or better yet, show how it doesn’t work based on the CSP algorithm, or by showing how the implementation doesn’t match the algorithm.

Why CSP matters

The point here isn’t that my CSP representation is a perfect model of my app and that my app must work in all situations because the model works. The point is that this CSP approach makes writing complicated concurrent or distributed systems easier. It is a relatively lightweight model checking approach that falls more in the category of advanced type systems than formal verification. We don’t need to manually manipulate math to see that our algorithm works. We just write a program in a funny (but modern) language, write tests in the form of assertions, and have our model checker brute force it to see if our tests pass or fail.

Porting the resulting CSP model to Clojure is relatively straightforward because Clojure’s core.async library is based on CSP. It would be even more straightforward for a CSP implementation in a language closer to CSPM like Haskell’s CHP. The matching of models means that CSP can be used to solve complex problems using core.async in a way that would be more difficult using another approach like functional reactive programming or actors. It’s not that you couldn’t do it, but impedance mismatch makes CSP modeling less useful. Translation between languages may take more work and it’s more likely that the program doesn’t actually match the model.

This is not a silver bullet. It’s easy for models to grow large enough to make them time consuming to check, for instance. The practicality of this approach for my day-to-day problems is an open question. But the promise is tantalizing. Once I had sufficient understanding of how CSP and CSPM work, writing a model and a specification was relatively straightforward. It feels more approachable and practical than writing distributed algorithms in CSP by hand, without sacrificing the power of the approach. With specifications that don’t care about most of the implementation details, algorithms can be refactored without fear of breaking basic premises. Instead of relying on an ad hoc implementation of an algorithm that someone on the Internet wrote, trusting that they knew what they were doing because they used fancy words and worked at Google, we can modify and verify the algorithm ourselves. Or we can throw it out and write our own algorithm entirely.

This is why CSP matters.

This post is duplicated on both my blog and the Reaktor blog.

Footnotes

-

What we are actually specifying is much more precise than my hand-waving explanation. We are saying that our specification process failures/divergences refines our implementation process. For further detail I direct you to the Roscoe book, which provides precise mathematical definitions. ↩